Sunday, June 6, 2010

Prosperpina's Return

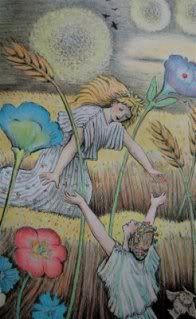

In Roman mythology, Ceres was the goddess of growing plants and mothering relationships, though she is perhaps most remembered as the mother of the abducted goddess Proserpina. According to the myth, the god of the underworld fell in love with Prosperina, kidnapped her, and made her his queen in the realm of the dead. Ceres, out of grief at the loss of her daughter, immediately stopped the growth of plant life on Earth and the world plunged into its first winter. Jupiter then intervened, persuading Pluto to return Proserpina to her mother, but not before the young goddess had eaten six pomegranate seeds from a tree in the Underworld. Having eaten the food of the dead, she was subsequently required to return to the Pluto for half of every year. In Prosperpina's absence, Ceres allowed the plants to wither and die, and upon Proserpina's return every year, spring came forth out of Ceres' joyful celebration.

I have an inkling of how Ceres must have felt. I can imagine that the annual wait must have seemed interminable, despite Jupiter's promise. Ceres must have worried that Pluto would renege, that Proserpina might decide to stay, that some chore would delay her daughter's return. This is spring for me on the farm: a season of worry even as the earth explodes with life. Until the first distribution, I am forever afraid that something will go terribly wrong and I'll be left standing by a barren, blighted field. Every little mishap leaves me questioning my skill as a grower--why are the peas still so short? Will the cauliflower recover from the frost? My spinach is growing too fast--what if it bolts before the rest of the crops are ready for distribtion? I'm a mess, constantly swinging from joy in the spring to despair that I will ever reach June.

On Friday, however, we had our first distribution. My spinach was huge, but delicious. The Turnips were sweet (and almost softball-size thanks to our strange, warm weather). We had bok choy and head lettuce and radishes and pea shoots. I was content. Prosperpina has returned to the world and life can go on.

Wednesday, May 19, 2010

The Best Man is a Horse

Then, two rows into it, having planted perhaps 25 pounds of the 300 we had, the tire blew out. And the rim snapped. The tractor limped to the edge of the field and died. All of the other tractors were too large to sub in for the job, and I mentally prepared for the Herculean task of planting the potatoes by hand: measuring beds, digging trenches, planting 275 pounds of potatoes. Katia, thankfully, had other ideas. “I could go put the gluesticks on the forecart...” she began. I tried to imagine how gluesticks might help the situation, and what role a forecart would play in that solution. Then I remembered: the horses. Best Man and Tina, Katia's working Morgans, are trained to pull a forecart and help with raking hay. Up to this point, they had been background creatures in the blur of my spring. I didn't have to feed them, and with hay-making not yet begun I had yet to see them in action.

Katia drove the horses up to the farm and we finished the job. There was a great deal of stopping and starting—the horses went too fast for me to keep the potato planter loaded, so I was forever calling them to a halt, restocking, and then taking off for another ten bumpy feet. Best Man found the whole process frustratingly slow, but he did his best to adhere to the program. In the end, the potatoes got planted.

This has been my season: harried, crazy, full of problems and equally full of make-shift, last minute, utterly wonderful solutions. I'm learning. The plants are growing. And now I need to weed...

Tuesday, April 27, 2010

Vegetable Musical Chairs

But lists are only as good as the circumstances they organize. My seeding plan, for example, was predicated on the assumption that we would have built our greenhouse in March, and it would be ready and warmly waiting for the seeding bonanza of April. That's not exactly how it worked out. Construction was postponed seemingly indefinitely—first because Brendan and Katia, through no fault of their own,were delayed in closing on their house (and the site of the would-be greenhouse). Then there was the problem of the frame, which we had planned to purchase from some friends who backed out the last week in March. We found a greenhouse company that promised to deliver on Saturday the 3rd, until they realized that we were in Hardwick Massachusetts, not Hardwick Vermont. April 1 found me without a greenhouse or a place to put it, watering my ever growing number of trays in a shower.

Change of plans. I drove to New Ha

Next we needed heat. An electrician lent us a propane heater, which we rigged up to provide warmth at night. The 200,000 BTU heater proved massive overkill, however, so I slept in a tent next to the greenhouse to monitor for melt down, and we left one roll-up side slightly raised to avoid cooking the plants. All seemed well—my plants were shooting up and my greenhouse finally felt like a proper structure. Until the heater ran out of propane Thursday night. One week's supply had cost $85, so we knew that our jury-rigged system needed changing. Besides, I didn't relish the thought of driving an hour and a half to the propane dealers each week with a 100 gallon tank in the back of the truck.

We called the propane company and asked them to

But Sunday morning, having worked a seventeen hour day the preceding day (which was my birthday), I decided to stop. We went out for ice cream. I ate food while seated. I went for a walk and admired the fresh green that comes and goes so briefly each year. Then this evening I sat down to make my list for the coming week.

Sunday, April 11, 2010

The View from Tuesday

Friday, April 9, 2010

How Badly Do You Want It?

As a farmer striking out on her own this year, I'm building everything from the ground up. I've got visions for implementing and improving on all of the good systems of Caretaker and Serenbe, but right now, I'm about as far from the fine-tuning stage as you can be. I'm still charging forward at full throttle, seeding flats even as I mentally scramble deciding where they will go. I'm watering plants in a shower with a showerhead, toting them back and forth from the bathroom as the sun or the woodstove dries them out. My planting “apprentice” is a three-year-old, whose primary task is to warn me if his one-year-old brother breeches my ottoman blockade and charges my growlights. A friend in Athol is babysitting eight flats of onions and two lettuce trays; as soon as I had sent them off, I seeded beets, cauliflower, peppers, parsley, and chives. My lights are full again.

Meanwhile, my greenhouse is in pieces, finally here, but still far from built. After a shipping snafu delayed what was supposed to be a Saturday delivery, I took matters into my own hands and drove to central New Hampshire to pick it up. For the record, a 17 x 20 foot greenhouse does fit in the bed of a Toyota Tundra—just not very gracefully.

Up at the farm, the rye grass that blanketed my field all winter is beginning to take off: thickening, greening, growing taller every day since the rains let off on Wednesday. I, meanwhile, am itching to till. Rye grass residue naturally impedes seed germination, which is great as a weed suppressant, but not so good when you need to start direct seeding soon. There are strawberries that need to be transplanted, equipment orders still to call in.

Three days a week, as part of our arrangement with Brendan and Katia, I take the 4 AM chore shift: feeding calves, shoveling manure, and watering pigs while someone else milks. Andrew takes three other mornings and all of the afternoons. We're all various states of crazy transition: from winter to spring, from Williamstown to Barre, from a small, cramped house to a new, dilapidated home that would intimidate even the folks of Extreme Home Makeover. Through all of this, we're learning to live together, to respect boundaries, to find time and space for rest.

And it is April. Let the games begin.

Thursday, March 25, 2010

Secret Family Recipe (this is your only chance)

Buttermilk Wheat Bran Pancakes with Yogurt and Blueberry Jam

1 1/8 cup whole wheat flour

1/2 wheat bran (I grind my own flour, so I'm always looking for places to throw this in. You can also use wheat germ, which you can buy at a health food store)

1 T sugar

1 t baking powder

1/2 t baking soda

1/4 t salt

scant 1 1/4 cups milk + 1 1/5 T apple cider vinegar (the original recipe called for buttermilk, but my substitution worked great)

scant 1/4 c olive oil

1 t molasses

2 large eggs, seperated

Mix the milk and vinegar together in a small bowl and let sit for a few minutes. Mix the dry ingredients together in a large mixing bowl. Add the egg yolks, molasses and oil to the milk and vinegar and mix thoroughly. In a third bowl, beat the egg whites to form stiff peaks. Mix the wet ingredients into the dry until just moistened, then fold in the egg whites.

Heat a griddle over medium high heat until water drops dance on the hot surface. Lightly grease the griddle and cook the pancakes (I assume you all know how to cook pancakes...)

Serve the pancakes with plain yogurt and jam or syrup.

I would share a picture, but we ate them up too quickly for that!

Friday, March 5, 2010

Miso Soup for the Soul

But on occasion I too want good food fast, and since the closest thing to convenience food in our house are rice cakes, it takes a bit of creativity to make a simple meal in short order. On Monday, however, we stumbled across a formulation that is almost as easy as ramen and infinitely more delicious: miso soup and wasabi peas.

We'd love to make our own miso, and Sandor Katz provides helpful directions in his awesome book Wild Fermentation, but we've not yet acquired the requisite koji grains to begin. Once we do, we'll need at least two months to ferment sweet miso, or a full year to make a traditional salty miso. So until then we are purchasing our miso at the local co-op, where we happened to find it absurdly on sale one week.

Miso is traditionally a soybean ferment, though you can make an unconventional miso out of pretty much any legume or even barley. The koji grains (which, unfortunately, you will have to purchase unless you like next door to a miso shop, where the mold might naturally exist) consists of rice inoculated with the spores of Aspergillus oryzae. Fermentation actually renders soy products far more nutritious to a human digestion system, as it turns complex proteins into simpler, more digestible amino acids. This is why so many Asian soy products--tempeh, tofu, tamari/soy sauce, miso--were fermented. In the West, however, we seem to have missed the memo, as the plethora of unfermented soy products touting great health benefits is long and varied. Considering the fact that the United States is the world's largest producer of soy beans (92% of which were Genetically Modified Round-up Ready seed in 2008), is it any surprise that soy gets stuck into practically anything?

If you'd like to avoid the GMO soy bandwagon, however, miso and other traditionally fermented products are the way to do it. They are not only good for you (miso contains an alkaloid that binds with heavy metals to carry them from your body), but they taste wholesome and healing like homemade chicken soup. And miso is SO much faster!

An important thing to remember when making miso is never to let it boil. Part of the nutrient value of miso derives from the living bacterial culture contained in the miso paste (rather like the healthy bacteria in yogurt). If you boil the soup, your subsequent soup will be dead.

At its simplest, miso soup can be made by mixing one cup of hot water with 1 tablespoon of miso. This is delicious, yes, but not quite substantial enough for me to consider it a meal.

MK's Miso Soup Meal

(serves 2)

N.B.: my measurements are approximations. Taste and add more or less stock as you like.

3-4 cup fish stock*

1 T tamari or soy sauce

2 T miso

1 carrot, finely diced

scallions, finely diced (optional)

Feel free to throw in other things if you have them: Chinese cabbage, diced daikon radishes, seaweed such as kombu or wakame instead of the fish stock, shitakes mushrooms, tofu, garlic, greens, tahini, or a dash of fish sauce. In other words, you can eat miso every day and it never taste the same...

Bring the fish stock to a boil, and add the carrot. Cook until soft. Remove from heat and let the stock cool down a bit. In a small bowl on the side, mix a few tablespoons of stock with the miso until fully combined. Add the miso and soy sauce and scallions back into the stock. Serve warm.

*We got fish heads from Dean and Deluca in New York City for free. And they were covered with extra fish meat, which we were able to pick off after we had made the stock and use late for fish cakes and whatnot. So wonderful, hearty fish stock can be yours for nothing more than a little bit of time and a slightly fishy smell in your kitchen.

Wasabi Peas

Oh man....I used to love those little morsels from Trader Joes: the blast of horseradish heat that fades away quickly into a crunch. But you don't have to buy them, I am happy to report--you can make them yourself in no time at all. Though, FYI, these will not be crunchy. This recipe is from my new Mollie Katzen cookbook The Vegetable Dishes I Can't Live Without, which I highly recommend.

1-2 t unsalted butter

1 cup minced onion

1 lb green peas (defrost frozen peas in a colander with warm water)

salt and pepper to taste

2-3 T wasabi paste (it comes in little tubes at the grocery)

1 T olive oil

3 T water

Melt the butter in a large skillet over medium heat. Add the onions and cook for 5 minutes over medium heat, stirring often so that they don't burn. Add the peas and any salt and pepper and cook for a further 5 minutes.

Meanwhile, place the wasabi in a small bowl and mash it with the olive oil. Add water by the tablespoon until the mixture becomes a supple sauce, pour this into the peas. Stir gently to coat. Turn the heat to low and cover the pan. Cook for 10 minutes.

The longer you let the peas sit after cooking, the more the flavors will milk. Serve warm.

Friday, February 19, 2010

Gone From My Sight

When we arrived, my Uncle was waiting to usher us along the corridors and into the small room where my grandmother lay. Suspended in a half-life of oxygen tubes and painkillers, she was not able to speak or greet us. She seemed hollowed out, breaking and broken.

So I did what she would have done for me, what she had done for me since I was a child: I told her stories. I told her about my winter in the north, about making haggis, about the farms where I have worked and where I will work next year. I reminded her of the fourth of July when she let me dye the applesauce blue (I was alone in my patriotic zeal, judging from the leftovers). I thanked her for the gingerbread houses that we made together every Christmas. When I had run out of stories, we sat quietly for a while. She didn't need any more stories distracting her from the work at hand. She needed all of us to let go, to relinquish the ties that were binding her to that room. As I struggled to find the words to release her, I was suddenly reminded of the owl we had caught one fall morning at Serenbe more than a year ago.

When we found him, the owl could only blink at us, his yellow eyes fierce and frightened: Samson shorn of his locks and chained to the temple pillars. In the night he had hunted our chickens, swooping low and soundless. He had found our fence instead—a lightly electrified net surrounding the chicken pen, erected against just such intruders. The nighttime struggle could only have been epic, we surmised, for the owl lay mute and utterly still, swaddled tightly in a straighjacket of his own devising. Upon our approach, he flexed his talons, tight across his chest, and opened and closed his beak soundlessly.

Realistically, we should not have helped this creature to get free. He was a predator, as likely as not to come back for a second helping. But we couldn't imagine any other action than to let him go. We carefully untangled the lines which pinned his wings at odd angles. We unwrapped the cords from his neck and legs. The final few knots wouldn't give to our ministrations, so against all better judgement, we cut the fence. By that point, it took two of us to hold the bird still. We could feel him gathering strength, straining for release. He seemed sound and unharmed despite his night in captivity, so we threw him into the air, watched his wings spread wide and catch against the air. He rose silently, purposefully, without hesitation.

My grandmother died Wednesday morning, some time between the last darkness of night and the first light of a clear day. I will miss her dearly, but I am glad to see her go.

Saturday, February 13, 2010

On Serendipity: A Retrospective

I believe in America’s agricultural revival. I’m 23 years old, the product of a small liberal arts college and a bustling, cosmopolitan graduate school, and I’m comparison shopping for work boots and overalls in preparation for my first day as a farmer. I’ll be honest; I don’t entirely know what I’m getting into. I grew up in the city, have never grown so much as a tomato. Call me crazy, but I actually believe that I can do this.Thus I began this blog, almost two years ago. Not many people actually read those words, however, as I only shared the address with my best friend and only then after oaths of strictest secrecy. For all of my posture of speaking from a soapbox, I was really writing to myself. I wanted to flex my writing muscles, which had finally recovered from the over-exertion of college and grad school. I wanted to remind myself why I had put development work on hold and moved to a farm. Spring was rising in me like sap, and I needed some forum to record my own greening.

At first, I was nervous to let my words loose in the world--what if I offended someone? What if my writing sucked? What if, someday, a stranger showed up on my doorstep professing psychic kinship and asking to stay for dinner? Still, that inevitable writerly urge stirred in me to find an audience. When Paige offered to link to this blog from the farm's website, the temptation proved too much to resist. My first comments thrilled me (they all still do), so when another greenhorn future-farmer from California complimented my blog and asked me for more information about Serenbe, I was happy to oblige.

Ok, so I did think he sounded a little bit over-eager, claiming "we-have-a-lot-in-common". Blogs are like one-way mirrors in that way--but after a few wary emails I became convinced that he was neither a serial killer nor a weirdo. He was planning to WOOFF his way around the US, volunteering on diverse farms in diverse regions in an attempt to discern his own niche within the broad discipline of agriculture. He hoped to come work at Serenbe for a month, before moving on to Florida and then along the Gulf coast. He liked rhubarb and vegetabling off, sure signs that he had at least a modicum of good taste. Paige figured we could use the extra hands in October, and she and Jack were having a very good time calling this person my "online boyfriend," so she hired him.

With that settled, we all moved on with our summers. The teasing settled down (or, to be more accurate, was directed toward other fronts), and I went on several bad blind dates. At the end of September on an early Sunday, I pulled up to the Greyhound bus station in Atlanta to pick up our new farmer. He was a study in reticence, pausing before any reply, thoughtful in the face of my exuberant stream-of-consciousness dialogue. I thought he seemed nice enough, though much quieter than I had expected.

Fast forward to Friday of last week. In the middle of a snowy meadow with a ring he had carved from a Hershey's kiss, Andrew proposed. Best Valentines Day ever? You betcha.

I found out, much after the fact, that he had chosen Serenbe as much for my words as for the farm. As he claims, "I just wanted to meet the girl with the blog." I am grateful that I was not made aware of this fact any earlier, however, as I would have doubtless done everything in power to sabotage his application, had I known his true motivations. In retrospect, I cannot think of a better way to meet your best friend and the person you most love in the world than this: first through the medium of your thoughts best-said, then through toil, working side-by side, and finally in the kitchen: chopping onions, debating politics, washing the dinner dishes before dessert.

Thank you everyone for reading. And most especially Andrew, thank you.

Wednesday, February 10, 2010

The Breakfast of Champions

I mention my breakfast not to inspire envy in the stomachs of the less snow-bound, but to share my excitement over my creation of real buttermilk. Buttermilk from the store is something of a misnomer--it is actually a cultured milk product, a thinner version of yogurt. Traditional buttermilk, on the other hand, was the byproduct of buttermaking. Once the fat globules in cream had been churned into a golden hunk of butter, the remaining liquid could be set aside as buttermilk for use in cooking. Without refrigeration, cream soured and thickened under the action of benign lactic-acid bacteria. When that soured cream was churned, the resultant butter and buttermilk took on a deeper, fermented flavor which many cooks came to love (along with the leavening action caused by the interaction of acidic buttermilk and basic baking soda).

I mention my breakfast not to inspire envy in the stomachs of the less snow-bound, but to share my excitement over my creation of real buttermilk. Buttermilk from the store is something of a misnomer--it is actually a cultured milk product, a thinner version of yogurt. Traditional buttermilk, on the other hand, was the byproduct of buttermaking. Once the fat globules in cream had been churned into a golden hunk of butter, the remaining liquid could be set aside as buttermilk for use in cooking. Without refrigeration, cream soured and thickened under the action of benign lactic-acid bacteria. When that soured cream was churned, the resultant butter and buttermilk took on a deeper, fermented flavor which many cooks came to love (along with the leavening action caused by the interaction of acidic buttermilk and basic baking soda). Somehow, despite the fact that I milked a cow last season and had ample opportunity to make my own butter, I never actually did. Whether this has anything to do with my overfondness for ice cream, I cannot say. Six months later, having acquired fresh cream and a proper spirit of inquiry, I finally got the job done. Along the way, I used a photo series I found here to guage the transformation of my cream into butter--I had been warned that if you churn it too long, the butter will separate back into cream, never to become butter again. Ten minutes in the Cuisinart was all I needed to produce a ball of buttery bliss the size of a clementine (it took me a bit longer than it should have, as I in my paranoia kept stopping the machine to peer inside and check for doneness). I squeezed out any residual buttermilk, rinsed the butter under ice water until my fingers went numb, and packed my little treasure away in the fridge. The whole thing was uncommonly simple, though butter-making limitations in my kiddie-sized food processor have me now jonesing for one of the huge 10-cup models.

I chose to make sweet cream butter from unsoured cream, so my buttermilk was correspondingly thin and fresh. Had I known that I would get the next day off, I might have left it out overnight in hopes of it thickening and souring for breakfast.

Milk and milk products are especially on my mind as of late thanks to the addition to our library of Milk: The Surprising Story of Milk Through the Ages by Anne Mendelson. Exalting in the compendious collection of milk lore, science, and recipes (!!!), I briefly considered making it my mission to try all 120 recipes in the coming season. Sanity, thankfully, intervened, reminding me that 1) I will almost certainly not have time for such gastronomic revels 2) my readership might grow just a wee bit bored with 120 dairy recipes, varied as they may be, and 3) that blogging your way through a cookbook is so 2002. Thus while exotic dairy products will undoubtedly creep back into the pages of this blog, I will continue to offer a wide variety of recipes for the vegetarian, vegan, lactose-intolerant, and full-blooded carnivores among you.

Tuesday, February 2, 2010

Iron Chef: Haggis Challenge

In case you missed it, Burns Night (anniversary of the birth of Scotland’s national poet, Robert Burns) was celebrated last week on the evening of January 25th. Beyond an excuse for bagpipes, excessive whiskey toasts, and a dusting off of the old tartan, Burns Night has the unique honor of being the only holiday in which organ meats feature prominently on the menu. Burn’s mock epic, “Ode to a Haggis,” has attached itself so securely to the day, that one cannot mention Burns Night without uttering “haggis” in the same breath. To celebrate Burns Night without that “Great Cheiftan o’ the Puddin’ Race” would be tantamount to Valentines Day without conversation hearts—sure, most people don’t really like to eat the chalky candies, but they’re such handy conversation starters, right?

And a haggis, allow me to add, is much, much more than a conversation starter. The recipe varies depending on whom you ask, but usually involves some combination of sheep heart, liver, tongue, kidneys, and lungs, all of which are combined with steel-cut oats, spices, and a generous portion of fat, then boiled like a pudding within a sheep’s stomach. Small wonder that the colloquial description claims that haggis contains “everything but the baaaa”. Traditional haggis was peasant food, and so not an exacting science; it utilized whatever was left once the “good parts” had been consumed. All manner of variation exists in present-day Scotland, from “beef haggis” to “vegetarian haggis” to “haggis burgers” (I don’t know that I want to know). Still, the ideal was and always shall be the spectacle of a haggis on a platter, sliced open like a sausage and steaming before the guests.

As you probably guessed, I really wanted to eat a haggis this year. Despite rumors to the contrary, the USDA had no plans of lifting their decades long ban on haggis imports (begun during the days of foot-and-mouth fears), so I took it upon myself to make one from scratch.

Farmer friends informed me that they would be sending a sheep to slaughter in January, and I quickly requested that they reserve all offal for me. Unfortunately, the watchful eyes of the USDA decreed that the stomach was unfit for stuffing and that lungs are not for eating, and I was only able to acquire the conventionally edible parts (heart, liver, kidneys, tongue). The lovely thing about organ meats is their relative economy, even when sourced from an otherwise expensive retailer. Purchasing enough lamb or mutton to host a dinner party would have placed quite a strain on my careful winter budget, but haggis supplies from a local farm whose grass-fed sheep had been slaughtered at a USDA facility (this adds quite a bit of cost for the farmer) set me back only $10.

Home, and having sufficiently exhausted the comedic photo potential of the tongue, I began my haggis. First, I boiled the offal for about three hours, ostensibly to render it more tender (though in truth it could only ever be described as chewy). Once cooked and cooled, I minced all of the organs and mixed them with toasted oats, spices, onion, broth, and some tallow. The mixture looked a bit like chunky sausage filling, and smelled surprisingly appealing, I thought. Lacking a (sheep) stomach, I had to take some culinary liberties, and I cooked the haggis double-boiler style, with tin-foil tightly covering the top of the haggis-bowl.

Home, and having sufficiently exhausted the comedic photo potential of the tongue, I began my haggis. First, I boiled the offal for about three hours, ostensibly to render it more tender (though in truth it could only ever be described as chewy). Once cooked and cooled, I minced all of the organs and mixed them with toasted oats, spices, onion, broth, and some tallow. The mixture looked a bit like chunky sausage filling, and smelled surprisingly appealing, I thought. Lacking a (sheep) stomach, I had to take some culinary liberties, and I cooked the haggis double-boiler style, with tin-foil tightly covering the top of the haggis-bowl.Our guests arrived. The whiskey poured. We heaped the table high with other vaguely Scottish delights in hopes that a failure of the haggis would not spoil the entire evening. And with great fanfare, we all dug in.

I’m not kidding, it was good. As in, people took seconds good. Andrew ate thirds, though that wasn’t terribly surprising, really. The surprise was universal, as almost everyone, it turned out, had partaken under the assumption that this would be a meal for bragging rights, rather than gastronomical enjoyment. I won’t tell you that the haggis was pretty, as it was not. And it did have liver-y overtones (you can never hide a liver, no matter how hard you try). But I can easily see why Scotland has adopted haggis as their national dish: a culinary emblem of resourcefulness, an ode to cereal and sheep.

Besides, haggis is way, WAY better than the South London standby of jellied eels.

DIY Haggis

1 sheep heart

2 sheep kidneys

1 sheep liver

1 sheep tongue

1/2 lb suet (lacking proper suet, I used a combination of tallow and lard)

1 cup toasted steel cut oats

2 onions, chopped

~1 cup beef broth, or cooking liquid from the offal

1/4 t ground allspice

1/4 t ground nutmeg

salt and pepper to taste

1 sheep stomach (optional)

First and foremost, be sure to source your offal from a farmer or butcher you know and trust. Consider that the liver is the of the body--do you really want the liver of an animal that was suckled on preventative antibiotics?

Cook the organs (NOT the stomach) in a pot of boiling water for 3 hours, approximately. They should be cooked through. Drain and reserve the cooking liquid, if you want. Once cool enough to handle, peel the tongue (yes, it will be disturbingly tongue-like), cut out the gristly center of the kidneys, and mince everything as finely as you can. This is the most labor intensive part of the process, by far.

Grate or chop the suet finely. (N.B: real suet is the fat that surrounds the kidneys of a cow. It melts, I am told, at a higher temperature than other beef fats, making it desirable in puddings for texture. Suet is not a hugely popular item in this country, so if you, like me, have trouble locating it, just use the closest thing in your larder.) Mix the suet, onions, spices, and oatmeal with the minced organ meat and moisten it all with the stock. Stuff the stomach. Stitch the stomach tightly shut, and prick it a few times to allow pressure to escape during cooking. Boil the stomach gently for about 3 hours. If you are thwarted in your quest for a stomach, I recommend the double boiler method, and I have heard rumors that it is even possible to cook a haggis in a crockpot (maybe next year). Place the haggis in your double boiler, cover the top tightly with a lid or tinfoil and a rubber band, and boil the haggis in your double boiler for 3 hours. Then serve and enjoy! Haggis is traditionally accompanied by mashed "neeps and tatties" (potatoes and turnips) and a generous dram of whiskey.

Sunday, January 24, 2010

Beantrees

I've been fortunate this winter, in that I've accumulated a small collection of second-hand seeds from Don, my former boss, and Katia, my future co-farmer, as well as some odds and ends I've picked up froms seed swaps and conferences. Second-hand seeds are the remainders at the end of the season, which, while not ideal, are still perfectly good, if you don't mind a little uncertainy in germination rates. I did some research about seed viability rates and set to work sorting my seeds into keepers and tossers.

Only, I have a really hard time throwing away seed. Even when I know it's virtually useless (onion seed, for example, is generally worthless after one year. So onion seed from 2006 will unquestionably suck), I kept pushing my tossers into a third pile, the "don't expect much from them, but hey, maybe a few will sprout?" group. I have a sneaking suspicion that a similar lack of willpower may account for Don's including 4-year-old onion seed in his gift to me...

Gradually, my collection took on a semblance of order, neatly sorted by family and best-by year. At the bottom of a box stuffed with empty seed envelopes from past years and some free samples packets of mixed greens, I stumbled across a strange treat: an unlabeled envelope from a 2008 seed swap. At the time of acquisition I was apparently without either a pen or good information, for the seeds within are completely anonymous, unanchored from variety name or grower identification. A few look to be parsnip seeds (no good by now, most likely), and some others are identifiable as lettuce, though no telling of what stripe. But then there are four huge red beans, lightly speckled with a few black streaks. I immediately thought of the story of Jack and the Beanstalk, imagining my little beans twining out a window and over the snow, climbing up into the clouds to fame and fortune. I tucked my mystery beans safely away for spring.

Wednesday, January 13, 2010

The Deep Freeze

I came out into the snow and felt the first pangs of the winter farmer doldrums. Thus far, long- anticipated rest and other seasonal distractions have kept me from missing the dirt. Besides, I've been more than sufficiently busy, between planning next season, visiting family, and (lately) substitute teaching sixth grade math. But the numbers finally got to me. I'm tired of Excel spreadsheets, converting yield per foot into pounds of seed per acre. I'm overwhelmed by seed catalogues and their relentlessly positive descriptions. I'd like some more kale to accompany my veal and potatoes. Watching "Dirt!", I felt envy rise in my chest at the muscles and tan lines of farmers. I'm winded by a romp in the snow, and I haven't lifted anything heavier than a cast iron skillet in months.

I have a plan, however. As soon as I am unemployed again (but before the financial ramification of this state have fully sunk in), I'm buying some dirt. Potting soil, some trays, a few more sprouting jar lids. I'm going to fire up the grow lights that Andrew's grandmother donated to the cause, and I'm going to grow. I'll start my onions, certainly, but I think I'll throw some greens into the mix as well. Maybe a kumquat tree for the corner? Or perhaps I could convert the defunct front porch to our cottage into a very cold cold frame?

Then again, I might feel completely satisfied simply to sit on the kitchen floor with a handful of finished compost, entranced by the sweet promise of fecundity.